The Florida Landscape

A Wet Desert

All of Florida has been a beach at one time, some places just haven't seen the tide in a few thousand years.

As sea levels have risen and fallen over thousands of years, the Florida peninsula has changed dramatically in size. When sea levels were lower, it was much much wider than it is now. There was also a time when most of the peninsula was underwater except for a few places in central Florida that became islands.

Centuries upon centuries of tides deposited large amounts of fine white sand across the peninsula. This means that nearly all the upland soils (ie, not swamps) are what we call sugar sand. You can see the white sand below in this picture of the entrance to the Juniper Prairie Wilderness in Ocala National Forest.

The plants in this picture are small and thorny with tough leaves. Many of them appear dead and there are few tall bushes or trees. This is a landscape reminiscent of a desert, not a sub-tropical paradise.

The fine sugar sand does not retain water very well. Rain water soaks down through the soil very quickly and enters the aquifer, and so despite torrential summer downpours, the soil remains very dry. Plants must be adapted to dry conditions or have tap roots to reach watercourses deep underground. In effect, this means Florida can be thought of as a wet desert.

A Land of Subtleties

Because water is scarce, plants have adapted to very specific levels of water. The most incremental changes in topography mean there will be slightly more or less water in the soil and so in true Florida wilderness you often see formations such as the one below.

I took this picture in the Juniper Prairie Wilderness. There was a slight depression in the land, completely unnoticeable if not for the changing plant species. In the center of the ring were plants that require the most water to survive. The plants in the next ring need slightly less water. The plants in the next ring need slightly less water, and so on. You find this delineation of plant species all the time in the Florida wilderness, but usually not in perfect circles like in this picture.

Sometimes I hear people bemoan our lack of dramatic views. Yes, Florida lacks mountains and everything that comes along with them: waterfalls, cliffs, snow-capped peaks, et cetera, but an appreciation for the subtleties of the landscape and the ways in which life has evolved to fit them will reward the thru-hiker.

A Land Dependent Upon Fire

Americans who live west of the 98th meridian are familiar with fire-dependent ecosystems, but east of the Mississippi such ecosystems do not exist—except in Florida. Florida's ecology has more in common with California than it does Georgia and Alabama, it's closest neighbors. This is because of the dry conditions created by the sandy soils described above.

Florida has both dry soil conditions and intense lightning storms. Tampa Bay, where I live, is the lightning capitol of the US, and second in the world for lightning strikes. After thousands of years of wildfires triggered by lightning, Florida's upland ecosystems are not only adapted to dry conditions, but to fire as well. Plant species like sand pine and wiregrass need the intense heat of a wildfire to open their cones and flower. Without regular fires, they do not reproduce. Californians will be familiar with this, since its jack pines and chaparral forests are also fire-dependent.

This dependency upon fire was not fully understood or appreciated until the past few decades. Many years of intense wildfire suppression and prevention created damaged ecosystems and dangerous conditions. Today, state government agencies have programs to deliberately set fires in order to mimic nature without the dangers of a true wildfire. These prescribed burns can create difficulties for thru-hikers, which I describe on the Problematic Trail Conditions page.

Landscapes of the FT

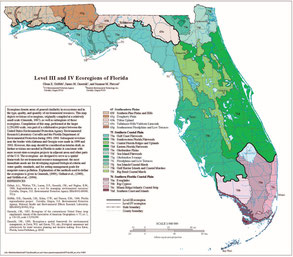

This map from the EPA shows the different ecological regions of Florida. If we follow the route of the FT across this map, we see how the trail traverses a diverse number of ecosystems.

This is a unique experience for hikers. On a trail like the Appalachian Trail, the ecosystem is basically unchanged until the hiker reaches the high elevations of the Smokies and White Mountains, and the far northern latitudes of Maine. On the FT, hikers constantly leave and enter new and distinct landscapes.

Based on articles from the University of Florida, those distinct landscapes are describe below in the broadest possible terms, roughly in the order a thru-hiker would come across them while hiking south to north. A swamp in south Florida will be different from a swamp in north Florida, of course; the Kissimmee prairies differ from the Ocala prairies. An entire book is needed to explore the many differences.

I simply intend to illustrate how the presence or absence of water creates dramatic differences in the land.

1) Swamp

The Florida Trail begins in the Big Cypress Swamp, and there is common confusion about the difference between a swamp and marsh. Both are wetlands, but while the Everglades is often called a swamp, it is in fact a marsh, because the water flows like a river. In a swamp, the water stands still.

Also, while marshes are dominated by grasses, a swamp is a forested wetland, populated by trees adapted to tolerate water levels that would drown other trees. The dominant trees in Florida swamps are bald cyress, pond cypress, and swamp tupelo. Sweetbays, willows, and red maples are also found there.

2) Freshwater Marsh

3) Prairie

4) Flatwoods

Millennia ago, sea levels rose and deposited a thick layer of sand across the flat expanses of the Florida peninsula. When the seas receded, few plant species could establish themselves in such sandy soil that retained little rainfall. Longleaf, slash, loblolly, pond, and sand pines however, with their long tap roots that reached down into the earth to water deep below, thrived. These pine forests, called flatwoods, pine flats, or pine barrens, covered half of Florida before European settlement.

In old-growth flatwoods, the pines are far apart, the understory largely empty, and the forest floor carpeted in grasses like wiregrass. When Europeans arrived in covered wagons, they could drive the wagons straight through the forest. Most of the peninsula was later clear-cut by loggers, and today's second-growth flatwoods are filled-in with shrubs while the trees are closer together. The Florida Trail does pass through flatwoods that resemble the primeval condition, however.

Fire is essential to the health and longevity of pine flatwoods. Regular fires keep the understory open and grassy by controlling the growth of woody shrubs, palmettos, sabal palms, and hardwood trees like oaks. One species of pine, the sand pine, requires the heat of a wild fire to burst its cones and release its seeds.

Scattered throughout the flatwoods are occasional small ponds where a layer of clay prevents rainfall from leaching through sand. The ponds may be seasonal or temporary, only holding only after wet season summer rains. Cypress grow within the ponds, as maples, bay trees, tupelo, and other hardwoods.

5) Scrub

Like the flatwoods, the scrub was created millennia ago when the seas rose and inundated the Florida peninsula. In the center of the peninsula was a ridge of sand dunes built over centuries. The

highest hills along this ridge became an archipelago of dry, sandy islands, and the plants and animals stranded there began to evolve in isolation. This was Florida's

ancient Galapagos, an engine of species diversification.

When the seas receded, the islands were once again united by land but the plants and animals remained (roughly) on those hilltops, now called the scrub. These unique species, called endemics, exist nowhere else on Earth, species like the scrub lupine, scrub blazing star, Florida grayfeather, pygmy fringe tree, scrub mouse, scrub lizard, blue-tailed mole skink, and the scrub jay. Between 40 to 60 percent of the species living in the scrub today are endemics, but two-thirds of the original scrub has been destroyed by development. It is the most endangered ecosystem in Florida.

The soil in scrub lands is fine white sugar sand, even more so than in the flatwoods. The sand holds no rainfall, and nutrients from rotting vegetation leach downward, carried by rainfall, never accumulating and enriching the soil, and so the scrub is like a desert. The plants that exist in this desert are called xerophytic (dryness-loving). Pines and oaks and shrubs that would grow tall in other locations are stunted, twisted, and gnarled from the harsh, dry, windy conditions. The only ecosystems I have seen that resemble it are alpine dwarf-forests, the Krummholz.

6) Bottomland Hardwood Forests

Bottomland hardwood forests are found along the edges of lakes and rivers and in sinkholes and are one of the lowest and wettest types of hardwood forests. Trees and plants in these forests have adapted to periodic flooding but cannot survive permanent inundation as in a swamp. Ecologically, these forests represent a midpoint between the dry uplands like flatwoods and scrub, and the flooded lowlands of swamps and wetlands.

Unlike uplands, these forests are not fire dependent, and wildfires rarely affect them for want of fuel. Leaves and dead wood on the forest floor are usually wet, unlike the tinderbox of dry litter in flatwoods or scrub forests. Infrequent fires allow the establishment of many slow-growing hardwoods, otherwise fast-growing pioneer species like pine would dominate.