Sanitation

You are your own biggest health-hazard in the backcountry. If you get sick in the backcountry, you probably did it to yourself through poor hygiene. Keeping clean is critical to a successful

thru-hike, and in this section we discuss pooping, washing, and laundry.

Women's Issues

The sanitation and related health concerns unique to women are discussed in our women's section. These include the possibility and benefits of peeing while standing up, preventing and treating vaginal infections in the backcountry, how to handle menstruation in the backcountry.

Clean Water

Clean water is of course important to sanitation, and we have devoted an entire page to it where we discuss the issue of avoiding polluted ground water. We also discuss water treatment in light of the large amounts of sediments and microorganisms in Florida water.

Pooping in the Florida Backcountry

Every trail has a different pooping situation. On the Appalachian Trail, there is a composting privy at every shelter except in Great Smokey Mountains NP. You almost never need to dig a cathole. On the other hand, the PCT has no privies and arid conditions combined a lack of cover change where and how you dig a cathole.

On the Florida Trail there is an occasional privy or bathroom at established campgrounds, but not many. You will be digging a lot of catholes. Fortunately the soil is soft, it's filled with organic material (except in the scrub), and decomposition happens quickly, making finding a good spot easy and easing the ethical concerns that trouble the PCT and CDT.

Digging a cathole correctly is important to prevent water pollution, stop the spread of disease, maximize the rate of decomposition, and avoid the bad trail karma of having another hiker find your poop. Here's how to do it:

1) Pick a Spot

- Walk at least 200 feet (70 paces) from the trail, campsites, and any body of water, including marshes and swamps.

- Similarly, the spot should be away from dry areas where water runs after a storm so that stormwater does not erode your cathole and carry feces into the nearest water source.

- Spot should be inconspicuous and out of sight

- Spot should not be somewhere a hiker might casually find it, like a potential campsite or clearing. In other words, it's in a place you would only go if looking for a poop spot.

- Soil should be deep with dark organic material. Organisms that decompose feces live in organic material.

2) Dig a Hole

- Use a trowel rather than a stick or the heel of your boot

- Hole should be 10 inches deep and 6 inches across. Most trowel blades are 6 inches long.

- Save all the dirt in a single pile

3) Bombs Away

4) Wipe

- Only use plain, unperfumed toilet paper so as not to attract rodents

- Baby wipes do a better job at cleaning, but must be packed out in a freezer-strength Ziploc bag because they decompose so slowly, even in ideal conditions. Never bury a baby wipe.

5) Stir

- Find a stick that is longer than the cathole is deep.

- Use the stick to stir together the poop and the TP, making it less likely an animal will dig up the TP

- Plant the stick firmly in the bottom of the hole. This is a signal to other hikers not to dig their cathole in that spot

6) Bury

- Completely fill in the cathole with the original dirt.

7) Naturalize the Site

- Cover the area with forest duff, pine needles, leaves, sticks, et cetera so that it looks natural, but leave the poop stick visible.

8) Sterilize Hands

- Use hand sanitizer rather than soap and water

The active ingredient in Purell and other hand sanitizers is ethyl alcohol (ethanol). These products are essentially just ethyl alcohol combined with lotion so the alcohol does not dry out your

skin. Every brand works equally well, so go with a generic to save money. A 2oz bottle is most convenient for backpacking.

Choosing a Spot

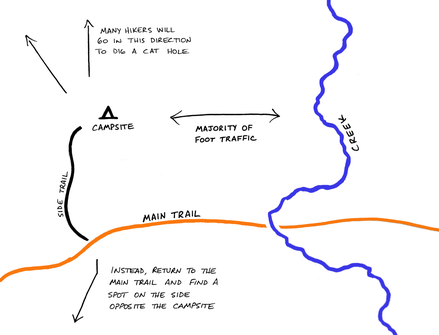

For whatever reason, people tend to stay on the same side of the trail as the campsite when they look for a spot. They also head away from the water source.

As a result, campsites are often surrounded by a semicircle of old cat holes. Clumps of used TP cover the ground not far from camp, either because rodents dug it up or because it wasn't buried properly in the first place.

To prevent this problem, we encourage everyone to go to the opposite side of the trail from camp then proceed another 200 feet.

Why Don't We Follow the Rules?

The process outlined above is pretty simple, so why do we still find tufts of white TP within sight of the Trail? Or worse, a semi-circular minefield of unburied poop and TP surrounding campsites?

Because it's an Emergency

If someone is uncomfortable pooping in a hole in the woods, they put it off as long as possible until it becomes an emergency. When the urge is finally irresistible, a mad dash into the woods doesn't leave much time to find an appropriate spot or dig a hole correctly. To avoid mad dashes, we recommend having a regular schedule — go at the same time every day, regardless of whether you feel an immediate urge. It can be in the morning, midday, or evening, whatever works for you.

200 Feet From Water, However...

The Florida Trail presents hikers with an ethical dilemma. Sometimes, you physically cannot get 200 feet from a body of water. This is especially true atop the Hoover Dike surrounding Lake Okeechobee. On one side is the lake, on the other side a canal. The dike itself isn't 200 feet across.

The Big Cypress Swamp presents an even more frustrating challenge, because there are a few places where the only dry land for miles is a small tree island, which is your campsite. The island is too small to get 200 feet away from camp, and all around you is water. The National Park Service does not address the issue at all on its website, but simply repeats the 200 feet rule and links to the Leave No Trace website. Calls to the park for comment were not returned.

It may come to pass that Big Cypress hikers will be required to pack out their poop in a wag bag, as PCT hikers summiting Mount Whitney are required to do.

Lightweight Trowel Options

Deuce of Spades

0.6 oz

6.8" long

aluminum

Montbell

1.4 oz

6.3" long

stainless steel

Coghlan

2 oz

10.8" long

plastic

GIS Outdoors

3.1 oz

10" long

polycarbonate

Sea to Summit

3.5 oz

10" long

aluminum

Cleaning Cookware

Never wash dishes in streams or ponds. Not only does it pollute them, but no matter how clean and clear the water appears, you don’t know if fecal coliform bacteria, giardia, et cetera is floating around in it. You are potentially contaminating your dishes and making them less clean.

We also do not recommend washing pots and utensils with drinking water and soap. Doing so creates greywater waste that must be poured out onto the ground and left in the environment. Even

biodegradable soaps are still pollutants. Leaving them in the ground or in waterways is bad trail karma.

The best way to wash your cook pot is to pour drinking water into it, swirl it around, maybe use your finger to rub anything sticking to the sides, and then drink the water! There's no wasted

drinking water and food particles don't go into the environment. For some people there is an ick factor to this, but that "dirty" water is what you were eating before, but watered down. Try it

and you'll get used to it.

Laundry

Dirty Clothes Bag

It is important to carry a small dry bag for dirty clothes. Sweaty, smelly underwear in particular will contaminate your clean clothes if stored in the same bag. Think of your used underwear as a

contamination source and sanitation issue.

Detergent

We have discovered that laundry soap is often hard to find along the Florida Trail. Vending machines at motels and laundromats are often broken or empty. Even when working and fully stocked, regular Tide is the only option, so people with allergies are out of luck. We recommend including powdered laundry detergent in your maildrops to avoid the frustrations of not having detergent.

Soap

There are a half dozen different brands that sell the same concentrated "biodegradable" green soap in the exact same bottle — Coghlan's, Sea to Summit, Campsuds, Outdoorx, et cetera. The bottles are everywhere and are so common we don't second guess them. When we think of "camp soap" we think of a little green bottle. Well, we'd like to change opinions about that. There are serious problems with the little green bottles.

1. They are incredibly expensive. A three to four ounce bottle costs between three and five dollars. That's a dollar an ounce — yikes!

2. We don't know what's in them. Invariably, the containers say the soap is biodegradable, but they do not list the ingredients. Just because something can be broken down by microorganisms doesn't mean it should be released into the environment. Soap is a pollutant — it does not exist in nature. And so we have to think about our use of soap in the backcountry as a form of pollution and take steps to minimize the consequences of that pollution.

Common household soaps are out of the question for backcountry use. Dishsoaps (like Dawn) and detergents are petroleum-based and contain phosphorus, which fuels algae blooms in our waterways and kills plants and animals. We would like to know whether the generic green campsoap is petroleum-derived or contains phosphorus, but the packaging keeps consumers in the dark.

3. They're certainly not organic. Whatever they are, these soaps are not all-natural plant derivatives. They have the look and feel of industrially produced soaps.

4. They Require Rinsing.

No-Rinse Soap

There is an expensive no-rinse soap on the market that boaters and campers call "astronaut soap" because the bottle claims astronauts use it to bathe in space.

Dr. Bronner's famous castille soap can be used as a no-rinse soap. Dilute a small amount in water, spread that water on your body, and then wipe it away — no need to rinse.

Dr. Bronners makes an unscented version of its Castille soap, which we think is best for use in the backcountry since it attracts fewer critters during the night.

Never put soap in a waterway. It is unethical and illegal in many places.