Weather & Climate

Hiking Season

Many Americans move to Florida to escape cold climates in other parts of the country. Though they may flee the cold, they don’t necessarily embrace the heat and many Floridians stay indoors during the summer. Floridians look forward to the onset of fall the way a northerner looks forward to spring. Thus, Florida's hiking season is backwards from the rest of the country: late November to early April.

Humidity

It's Not the Cold, It's the Humidity

Florida’s thick humidity persists even in winter and presents a surprising challenge to staying warm. During winter, sweat and moisture from the air cling to clothing and do not evaporate, causing a persistent chill. The damp permeates everything, getting up under clothes and into sleeping bags. After hiking the High Sierras, the White Mountains, and Maine, we've found that 40 degrees in Florida is much colder than 40 degrees up north or in the high mountains where the air is dry. Think of it as an effect like wind chill.

It's Not the Heat, Either

In order to carry heat away from the body, sweat must evaporate. High humidity inhibits evaporation, as the already moist air will not accept more moisture, makes staying cool challenging.

To mitigate the humidity, we recommend the following:

- a synthetic rather than down sleeping bag — down absorbs moisture from the air and dries slowly

- a fleece jacket rather than a nylon jack stuffed with insulation — the nylon is clammy and does not carry moisture away from your body, additionally fleece insulates better when wet

- no cotton anything, even underwear

- sneakers instead of leather boots

Sunburn

After the summer solstice, the sun sinks closer and closer to the southern horizon until it seems to barely climb above the horizons at all — if you live in the north.

Florida's latitude of between 25 and 30 degrees means that even on the winter solstice the sun is still high and bright. It also means you can get sunburnt on a cloudy day. Counter-intuitive yes, but it has happened to us many times.

Nor do forests provide little respite from the sun. The Trail winds through pine flatwoods, which are so open that cars could easily drive through them, as well as scrubs and prairies that provide virtually no cover. Levy and roadwalks are usually exposed with no shade. Even Big Cypress, the great swamp, leaves hikers exposed to direct sun much of the time.

We don't recommend applying sunscreen every day — it's difficult to stay clean on a thru-hike and greasy sunscreen makes that all the more difficult. Instead, dress like the cowboys did: wear a wide-brimmed hat, a long sleeve shirt, long pants, and sunglasses.

Winter Cold Fronts

During the winter, temperature and rainfall fluctuate wildly but predictably throughout the week. About every 6-8 days a cold front arrives from the northwest, headed in a southeast direction across the state. This a fairly regular weekly pattern during January, February, and March.

At its leading edge are high winds and rainfall. Once these storms pass, freezing temperatures combined with cloudless sunny skies follow. Sunshine is still intense during winter, regardless of the temperature, and one can be easily sunburnt on these cloudless days.

The first day after a front is the coldest. Subsequent days grow progressively warmer. It is always hottest just before a front hits. The temperature swings can be wide — 80 to

30 degrees in a day.

Since fronts move at steady speeds, forecasts are accurate and you can plan to zero on the day one hits, rather than hike through freezing rain. Expect rains at the leading edge to be heavy like

summer thunderstorms.

The cold front pattern presents hikers with the problem of battling heat and humidity one day, only to turn around and fight to stay warm and dry when fronts hits.

Thunderstorms

On the Appalachian Trail, it often rains for days at a time, drenching hikers, but they slog on and deal with the dampness. On the AT, the biggest threat rain presents is a loss of core body temperature. A functional waterproof jacket and pants mitigates this threat. The rain on the AT however, even the heaviest rain, is a drizzle compared to a Florida thunderstorm. The rain here is more intense than people from out of state realize and it starts quickly.

Fortunately for thru-hikers, they do not have to contend with many thunderstorms, but the last 100 miles of the Trail can be very stormy. If a thunderstorm rolls in on you, do not keep hiking as if on the AT. Take cover immediately.

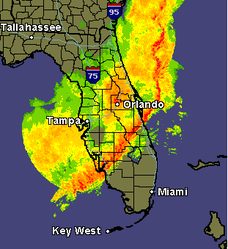

Central Florida lies at latitude 28 degrees north, a latitude shared with the Mexican desert, the Sahara Desert, and the Middle East — not places known for cool, damp weather. The only reason Florida is not a desert itself, is its peninsular shape, which creates thunderstorms.

During the day, the sun heats the land faster than the surrounding water. The air over the peninsula rises, and the comparatively cooler air above the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico rolls in to fill the empty space left by the rising air (low pressure in meteorological terms). As the two moist bodies of air collide they create huge thunderstorms. Like clockwork in summer months, this cycle plays out as thunderheads boil every afternoon.

While thunderclouds form every afternoon beginning around April, it doesn’t necessarily rain everywhere every day. The possibility of thunderstorms should not discourage someone from backpacking, but they can be violent, with high winds, pounding rain, tornadoes, and lightning.

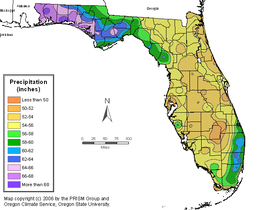

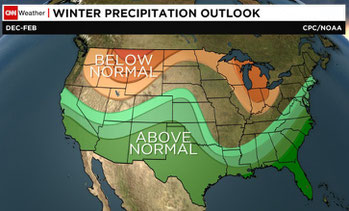

At roughly mile 1015, thru-hikers reach the town of Crestview, which has the distinction of being the rainiest place in Florida. As the map to the right illustrates, the far western panhandle, which is about trail miles 1000-1100 are the very rainy. Big storms are likely in late March and early April when thru-hikers are finishing.

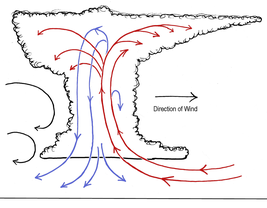

Downsdrafts = Time to Take Cover

How do you gauge the weather and know when it is time to take shelter? If you feel a sudden burst of cold air, that means a thunderstorm is right on top of you, is moving closer, and heavy rains will begin shortly. That burst of cold air is a downdraft — cooled air falling down through the storm from its top.

Surprisingly, There Can Be Flash Floods

Usually, Florida's flat terrain means rivers do not experience flash flooding. Small creeks may swell, but the highwater line is obvious and rarely will the creek swell over its banks since huge summer thunderstorms are a regular occurrence and the land is adapted to them.

However, the last roughly 250 miles of trail traverse surprisingly hilly terrain — the very edges of the Appalachian foothills. When thru-hikers arrive here, spring storms are appearing and can create flash floods. Do not camp right next to streams.

El Niño Years

In normal years, parts of Florida flood in the summer. During this rainy season lands swell with water and become marshes and wetlands, only to dry out during the winter. This is yet another reason to thru-hike in the winter, since so much of the Trail is flooded during the summer.

However, El Nino years disrupt this wet-dry cycle and make winters very, very wet. The Trail can be as flooded as you might find it in the summer, as was the case for hikers in 2015. Before your hike, see if that year is predicted to be an El Nino year and anticipate having wet feet.

Lightning

Tampa is the lightning capital of the United States and nearly every storm in Florida has lightning. Fortunately for Florida Trail thru-hikers, the most violent storms with the most lightning occur in the summer. Winter storms are mild, unless your hike runs into April when spring storms begin hitting the far western end of Florida (see above).

To reduce the likelihood of a lightning strike, take these precautions:

- During a lightning storm, do not continue hiking. Set up camp and wait it out.

- Avoiding high ground, water, solitary trees, open spaces, metallic objects. Search for low ground, ditches, and trenches. If they contain water or if the ground is saturated, then find clumps of shrubbery or trees, all of uniform height.

- Remove all metal objects, bracelets, watches, rings, and ditch your trekking poles.

- Avoid all metal shelters and sun shelters.

- If you are hiking in a large group, do not huddle together.